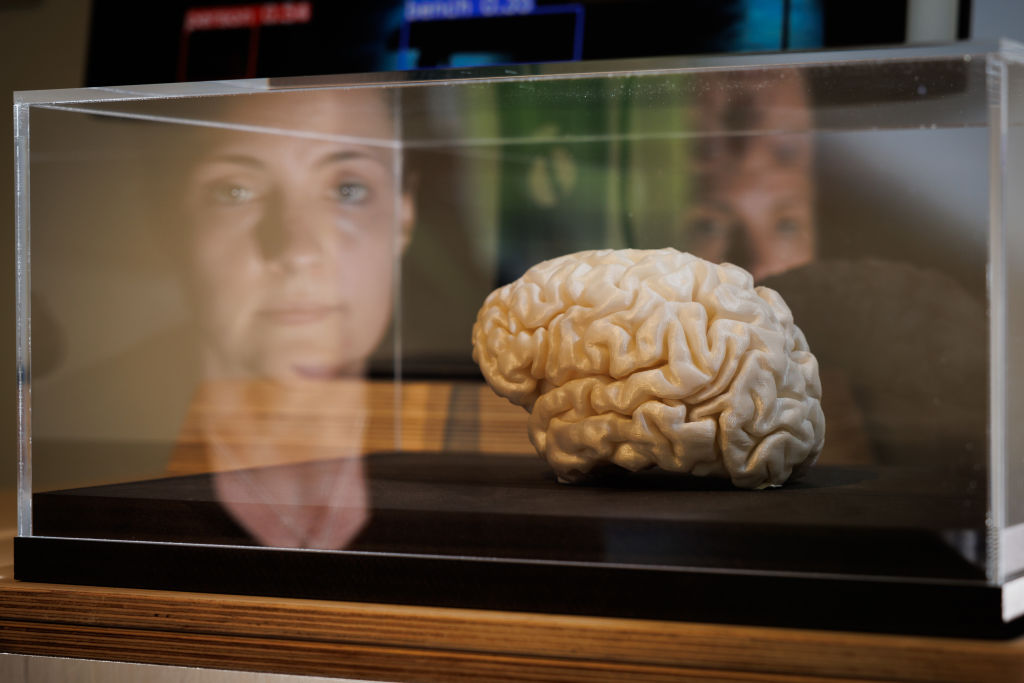

A team of scientists has uncovered new regions of the brain that support social interactions and are in constant communication with the ancient amygdala region—a discovery that could help treat psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression.

In a study conducted by Chicago-based Northwestern Medicine in the US, and published in the journal Science Advances, scientists sought to better understand how humans evolved to become highly skilled at interpreting what’s happening in other people’s minds.

“We spend a lot of time wondering, ‘What is that person feeling, thinking? Did I say something to upset them?’” said senior author Rodrigo Braga.

The brain regions that enable these abilities are part of the human brain’s more recently evolved areas, suggesting that this skill is a relatively new development in evolutionary terms.

“In essence, you’re putting yourself in someone else’s mind and making inferences about what that person is thinking when you cannot really know,” Braga explained.

The study found that the advanced parts of the human brain supporting social interactions—known as the social cognitive network—are connected to and in constant communication with the ancient amygdala.

Often referred to as the “lizard brain,” the amygdala is typically associated with detecting threats and processing fear.

“The amygdala is responsible for social behaviours like parenting, mating, aggression, and navigating social-dominance hierarchies,” Braga said. While earlier studies have observed co-activation of the amygdala and the social cognitive network, Braga noted that “our study is novel because it shows the communication is always happening.”

Within the amygdala, a specific region called the medial nucleus plays a critical role in social behaviours.

This study is the first to show that the medial nucleus of the amygdala is directly connected to newly evolved regions of the social cognitive network, which are involved in thinking about other people.

This connection allows the social cognitive network to access the amygdala’s role in processing emotionally significant content, the researchers explained.

Both anxiety and depression are linked to hyperactivity in the amygdala, which can lead to excessive emotional responses and impaired emotional regulation.

The study’s findings suggest that less-invasive treatments, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), could potentially use this new knowledge of brain connections to improve treatment outcomes, the authors noted.

(Inputs from IANS)