Pakistan, created in 1947 after the partition of British India, was a nation seemingly destined for further division. Many analysts considered it a geographical absurdity, a loose amalgamation of two separate territories 1,000 miles apart. Beyond sharing a Muslim majority, West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now known as Bangladesh) had little in common.

One of the most significant differences between the two regions was language, which became a major source of identity problems and fuelled Bengali nationalism among the people of East Pakistan.

While people in West Pakistan spoke Urdu, the main language in East Pakistan was Bengali. In December 1947, students at the University of Dhaka protested, demanding that Bengali be recognized as one of Pakistan’s official languages. This marked the beginning of the language war between East and West Pakistan. Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, responded by visiting Dhaka in March 1948 to deliver a stern message: Urdu would be the only official language of Pakistan. Moreover, leaders who spoke Bengali in the East Pakistan assembly were warned they could be tried for treason. Ultimately, West Pakistan imposed Urdu as the sole national language across both regions.

In response, the Bhasha Andolan (Language Movement) began in East Pakistan in 1952. This movement witnessed the deaths of many activists, politicians, and civilians due to atrocities committed by the West Pakistan-led regional regime. A key outcome of the language movement was the establishment of the Awami League in 1955, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

In 1956, Pakistan was established as an Islamic Republic with a new constitution. The country that year accepted Urdu and Bengali as official languages. In 1958, a military coup led by General Muhammad Ayub Khan abrogated that constitution.

The other big difference between the West and East Pakistan was the culture being followed by its people. Speaking a different language than West Pakistan, the people of East Pakistan followed a single ethnicity, Bengali, with a rich past. On the other hand, West Pakistan was a societal mix of people from different origins, including Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan, and Pashtun people from its border areas, the North-West Frontier Province. Culturally, the people in East Pakistan had a stronger sense of belongingness than those in West Pakistan.

Despite these big differences, there could have been a united Pakistan based on religious similarity if both territories were treated equally by the country’s political leadership. However, the united Pakistan failed miserably here. The two territories, separated by a thousand miles, with different languages spoken and cultures followed, were ruled by a unilateral political leadership from West Pakistan.

The top political lineage under Jinnah that united Pakistan followed was largely from West Pakistan only. Also, its military wing leadership, the army, the air force, and the navy were based in West Pakistan only.

These disparities manifested in the repercussions felt by East Pakistan from 1947 until its liberation in 1971 as Bangladesh. The West Pakistani leadership treated East Pakistan as a colony, extracting benefits while denying it the rights and resources it deserved.

EAST PAKISTAN WAS MORE PROSPEROUS THAN WEST PAKISTAN

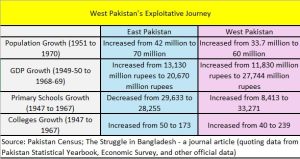

According to the 1951 Pakistan Census, East Pakistan had a population of 42 million, exceeding West Pakistan’s 33.7 million. Geographically, East Pakistan was a riverine territory with ample rainfall, making it more prosperous. Its fertile and productive lands stood in contrast to West Pakistan, which, aside from Punjab, was largely dry with barren areas.

Moreover, a study titled “The Struggle in Bangladesh,” published in the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, indicates that in the initial years, East Pakistan’s GDP surpassed that of West Pakistan. Educationally, East Pakistan also had an advantage.

Initially, in 1949–50, East Pakistan’s GDP was 13,130 million rupees, more than West Pakistan’s 11,830 million rupees. In education, East Pakistan had 29,633 primary schools in 1947, compared to just 8,413 in West Pakistan. Similarly, East Pakistan had 50 colleges, while West Pakistan had 40.

WEST PAKISTAN’S COLONY

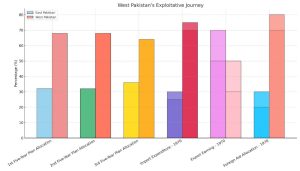

Despite East Pakistan’s higher GDP, better educational levels, and stable cultural heritage, data analysis reveals that West Pakistan monopolized industrialization and other benefits by installing a lame-duck government in East Pakistan.

East Pakistan was the primary source of jute, united Pakistan’s key export commodity. Logistically, industrial units for cotton textiles should have been developed there, but the country’s leadership chose to establish them in West Pakistan. Economic institutions and infrastructure developments, such as seaports, railways, and roads essential for promoting industrial growth further, were largely concentrated in West Pakistan only.

Conversely, East Pakistan experienced limited development, primarily aimed at supporting industries located in West Pakistan, according to the study. Furthermore, most industries in East Pakistan were developed by industrialists based in West Pakistan. Just 11% of industries were owned by Bengalis, making East Pakistan a labour hub for West Pakistan.

The deteriorating situation of East Pakistan over the next two decades reflects this exploitation. While East Pakistan was once more prosperous than West Pakistan, by 1970, the situation had reversed entirely.

Data from the study reveal that by 1968–69, West Pakistan’s GDP exceeded East Pakistan’s by 34%, and its per capita income was 62% higher. In united Pakistan’s first and second Five-Year Plans, 68% of the allocations went to West Pakistan, slightly reduced to 64% in the third plan. Pakistan’s economy largely depended on foreign assistance, of which 70% to 80% benefited West Pakistan. Although East Pakistan contributed up to 70% of Pakistan’s export earnings, 75% of imports were directed to West Pakistan.

CALL FOR SELF-DETERMINATION

These factors, language suppression, cultural differences, economic exploitation, mass arrests, killings, disappearances, and colonial treatment, left East Pakistanis facing an uncertain future after two decades of hostility.

In the 1954 regional elections, a coalition known as the United Front defeated the Muslim League, which had been based in West Pakistan and had ruled East Pakistan until then. In February 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of the Awami League presented his Six-Point Charter to the then-military ruler of Pakistan, Field Marshal Ayub Khan, demanding autonomy and greater control over East Pakistan’s economic affairs. These Six Points became central to Bengali nationalism and eventually transformed into a liberation movement following the 1970 general elections in Pakistan.

1970 PAKISTAN ELECTION: A TURNING POINT – EAST PAKISTAN’S CALL FOR INDEPENDENCE

Pakistan conducted its first general election on December 7, 1970, which is regarded as the most transparent election in the country’s history, according to Geo News, a major Pakistani news platform. The main contenders were Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), based in West Pakistan, and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League, based in East Pakistan. The Awami League achieved a landslide victory, winning 170 seats, while the PPP secured only 81.

Despite the Awami League’s clear mandate to govern all of Pakistan, the country’s military ruler, General Yahya Khan, and the PPP’s Bhutto opposed this outcome. They dismissed the election results and imposed martial law, denying the Awami League its rightful leadership.

This action led to widespread protests and riots in East Pakistan. In response, Sheikh Mujib initiated a civil disobedience movement. On March 7, 1971, the Awami League mobilized 50,000 Bengalis to start a peaceful protest in Dhaka. However, on March 25, 1971, Sheikh Mujib was arrested and airlifted to West Pakistan with the launch of Operation Searchlight.

OPERATION SEARCHLIGHT

Following Sheikh Mujib’s declaration of independence for East Pakistan, West Pakistan launched a brutal crackdown on Bengalis. Operation Searchlight, initiated by West Pakistan on March 25, 1971, stands as one of the most horrific state-run military operations in history. According to various investigative estimates, including the Russian newspaper Pravda, approximately 3 million East Pakistanis were murdered by Pakistani troops and supporting militias.

In the 1970 general election, West Pakistan-based parties failed to win any seats in East Pakistan, underscoring the widespread support for the Awami League and its pro-independence stance among civilians, police, and security forces in East Pakistan. Consequently, West Pakistan’s troops and supporting radical militias targeted these Bengali-speaking populations across the region.

Deploying hundreds of thousands of troops across Dhaka and throughout East Bengal, supported by air and naval power, the main targets were Awami League politicians, military personnel, East Bengal police, and Bengali-speaking civilians.

An analytical report published in the Dhaka Tribune indicates that one of Operation Searchlight’s objectives was to disarm and arrest Bengali soldiers and policemen serving in East Pakistan. Another aim was to attack Hindu-majority areas of Dhaka. On the night of March 25, 1971, casualty figures in Dhaka alone reached approximately 35,000.

During the nine months of the operation, hundreds of thousands of Bengali women were subjected to rape. According to a report in the Smithsonian, around 400,000 women underwent late-term abortions, although the actual number is believed to be much higher.

REFUGEES IN INDIA

The brutal crackdown compelled millions of Bangladeshis to flee to India. By May 1971, India was hosting 1.5 million refugees, a number that swelled to around 10 million by December 1971, making it the largest refugee crisis in the modern world. Internally, the military operation displaced approximately 30 million people within Bangladesh.

This massive influx placed a significant burden on India. Nevertheless, the country stepped forward to assist, despite lacking domestic laws to manage refugees and not being a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention or its 1967 protocol. India established 825 refugee camps across seven states, with 19 central camps capable of accommodating up to 50,000 refugees each.

ECONOMIC BURDEN

The economic burden was significant. India had to reassess its Fourth Five-Year Plan. The 1971–72 Budget stated, “The country’s resources, physical as well as fiscal, were greatly strained by developments across the border, the influx of nearly ten million refugees and the outbreak of hostilities in December 1971.” 1 Despite these challenges, the economy responded effectively, as noted in the budget document.

A World Bank assessment, based on 9 million refugees, estimated the direct cost to India at approximately US$700 million from April 1, 1971, to March 31, 1972, which equates to around US$5.5 billion today. India managed this expenditure largely through internal resources. According to a CIA document from March 1972, released in 2010, the Indian government spent about 4% of its planned central government expenditure for FY1971 on refugee care.

INDIA’S STAND

India supported Sheikh Mujib’s call for independence but initially refrained from participating in the war. Instead, it provided moral and material support to the independence movement. On April 17, 1971, a provisional government of Bangladesh was formed and relocated to Calcutta as the “Bangladesh Government in Exile.”

Meanwhile, the freedom fighters of East Pakistan formed the Mukti Bahini, an armed resistance movement against the West Pakistani military and supporting militias. Comprising members of the Bengali military, paramilitary forces, police, and civilians, these fighters engaged in guerrilla warfare.

India’s support bolstered their efforts. The geographical separation of 1,000 miles of Indian territory between West and East Pakistan meant that Pakistan could not easily reinforce its military presence in East Pakistan with additional air and naval power.

West Pakistan had previously exhibited hostility towards India, notably in the conflicts of 1947 and the 1965 war, which it lost. Its actions in East Pakistan heightened diplomatic tensions and prompted a military buildup in India.

The tipping point occurred on December 3, 1971, when Pakistan launched pre-emptive air strikes on Indian airfields. This act of aggression compelled India to formally enter the war, engaging its Army, Navy, and Air Force in a coordinated response to both the humanitarian crisis and threats to its national sovereignty. Before this, India had adopted a restrained approach, engaging in diplomatic efforts and appealing to West Pakistani leaders to create safe corridors for refugees to return. These appeals were ignored.

THE QUICK END

India’s entry into the 1971 war was driven by the humanitarian crisis and direct threats to its national security. By launching joint military operations with the Mukti Bahini, effective coordination and intelligence sharing were achieved, significantly disrupting Pakistani military efforts. Through a series of strategic offensives, the joint forces rapidly overran West Pakistan’s military presence throughout Dhaka and East Pakistan.

On December 16, 1971, Lieutenant General A.A.K. Niazi of Pakistan unconditionally surrendered to Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora of India, along with 93,000 troops, marking one of the largest surrenders since World War II. The war officially ended with India’s unilateral ceasefire on December 17.

WHY INDIA’S ENGAGEMENT WAS NECESSARY FOR A JOY BANGLA MOVEMENT

The success of the “Joy Bangla” movement on December 16, 1971, could only be possible with India’s commitment to the cause. With the onset of Operation Searchlight, India opened its borders to refugees, providing massive relief operations while simultaneously engaging in diplomatic efforts to resolve the crisis. Military intervention by India was the last resort.

The military intervention ultimately helped realize the goals of the “Joy Bangla” movement.

Twenty-three years of suppression, from 1947 to 1970, with West Pakistan ruling East Pakistan through military involvement, left the eastern territory with a strong desire for independence, an aspiration difficult to achieve in an economy controlled by West Pakistani industrialists and a polity dominated by a West Pakistan-based military ruler allied with exploitative politicians.

The increasing number of refugees in India proved the fact that there was no internal security structure and local and regional administration available for them to take over the West Pakistan-led apparatus.

Over ten million refugees fled to India in ten months, while thirty million were internally displaced. The refugee headcount included Bengali military wing officials, soldiers, and police personnel. According to the Bangladesh High Commission in London, thousands of families of officials, soldiers, and activists from East Pakistan were interned in West Pakistan. Killings and rapes became daily events of horror to be observed. India’s daily refugee count surged from 17,000 to 60,000, with numbers continuing to rise.

The freedom fighters of East Pakistan had the courage and will to fight for independence, but they lacked the strength of a coordinated war strategy and the full complement of military resources—army, air force, navy, arms, and ammunition—to defeat West Pakistan’s full-fledged military. They had to fight a country’s army that had exposure to past war experiences, something they didn’t have, as East Pakistan was not the war theatre of the 1965 India-Pakistan war. India’s decision to join the war after Pakistan’s attack on Indian territory proved to be the turning point, helping Bangladesh achieve a goal that once seemed unachievable.

Had the Mukti Bahini not received external support, Operation Searchlight could have seriously affected the East Pakistan freedom movement and its hopes to break the colonial shackles of West Pakistan.